Japan wins over China beyond South China Sea – for now

Two major powers in Asia, Japan and China have been all but bosom friends for centuries and now more so. Their rivalry range from fishing into each other waters to space research on one hand and dominance from the South China Sea to the Indian Ocean and may be beyond.

Two major powers in Asia, Japan and China have been all but bosom friends for centuries and now more so. Their rivalry range from fishing into each other waters to space research on one hand and dominance from the South China Sea to the Indian Ocean and may be beyond.

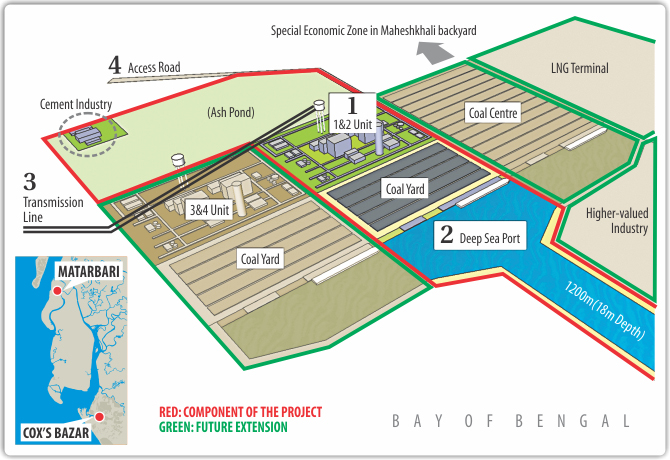

In one of the recent business competitions in the South Asian region Japan is beating out China in a race to build Bangladesh’s first deep-sea port as the region’s powers jostle for a foothold in the Indian Ocean.

Construction of the 18-meter-deep port at Matarbari on Bangladesh’s southeast coast is set to start by January 2016, according to the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA). That’s bad news for a stalled China plan to build a port about 25 kilometres away.

“I’d imagine there’s only room for one port,” said Krispen Atkinson, a maritime analyst at IHS Inc., citing the cost to build railway lines and approach channels. “There are probably political reasons behind it as well. If you’re looking to build a port and want Western support as well, would a port financed by China be the favoured option?”

The deal would mark a setback for China in South Asia, where it is seeking to establish economic and military ties in a region that carries about 80 percent of its oil imports. The Bay of Bengal, a body of water bigger than Mexico, lies at the heart of an area where China, Japan and India are investing billions of dollars to secure economic gains for decades to come.

“There’s a remarkable scramble going on,” said David Brewster, a visiting fellow at the Australian National University in Canberra, who called the bay a “twin” to the South China Sea. “The Japanese clearly see themselves in competition with China, and control over ports is seen as important. I expect the Japanese are very happy about this.”

Bangladesh’s government confirmed that work on the Matarbari port is scheduled to start early in 2016, while saying talks on the China-backed port at Sonadia island are still underway.

Bangla desh hasn’t built a new seaport since independence in 1971. It’s wanted a deepwater one for more than a decade as the country turned into the world’s second-biggest exporter of garments, which account for 15 percent of gross national product.

desh hasn’t built a new seaport since independence in 1971. It’s wanted a deepwater one for more than a decade as the country turned into the world’s second-biggest exporter of garments, which account for 15 percent of gross national product.

Waters surrounding Bangladesh’s two main ports — Chittagong and Mongla — are so shallow that vessels have to wait for an incoming tide to berth and an outgoing one to leave. Bigger ships currently need to transfer their loads to smaller vessels. The longer turnaround cancost an extra $15,000 per day, making Chittagong several times pricier than ports in neighboring countries.

The Matarbari port, at 18 meters (59 feet), would be deep enough to host the largest container vessels, according to IHS’s Atkinson.

Asian Century at Risk?

Asia’s robust economic performance over the three decades preceding 2010, compared to that in the rest of the world, made perhaps the strongest case yet for the possibility of an Asian Century, a phrase made an appearance in a 1985 US Senate Committee on Foreign Relations hearing.

Although this difference in economic performance had been recognised for some time, specific individual setbacks (e.g., the 1997 Asian financial crisis) tended to hide the broad sweep and general tendency. By the early 21st century, however, a strong case could be made that this stronger Asian performance was not just sustainable but held a force and magnitude that could significantly alter the distribution of wealth and power on the planet. Coming in its wake, global leadership in a range of significant areas—international diplomacy, military strength, technology, and soft power—might also, as a consequence, be assumed by one or more of Asia’s nation states.

A 2011 study by the Asian Development Bank found that an additional 3 billion Asians could enjoy living standards similar to those in Europe today, and the region could account for over half of global output by the middle of this century. It warned, however, that the Asian Century is not preordained. It is yet to be achieved and many including some real and serious challenges are yet to overcome.